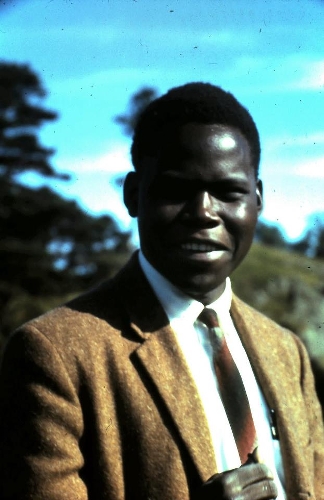

He possessed a five-day supply of food, a Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress (his two treasures), a small ax for protection, and a blanket.

With these, Legson Kayira eagerly set out on the journey of his life.

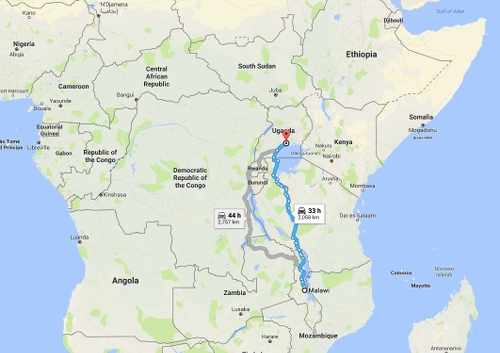

He was going to walk from his tribal village in Nyasaland (Malawi), north across the wilderness of East Africa to Cairo, where he would board a ship to America to get a college education.

It was October 1958. Legson was sixteen or seventeen, his mother wasn’t sure. His parents were illiterate and didn’t know exactly where America was or how far. But they reluctantly gave their blessing to his journey.

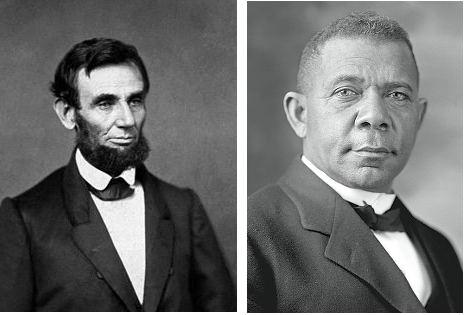

To Legson, it was a journey derived from a dream–no matter how ill-conceived–that fueled his determination to get an education. He wanted to be like his hero, Abraham Lincoln, who had risen from poverty to become an American president, then fought tirelessly to help free the slaves.

He wanted to be like Booker T. Washington, who had cast off the shackles of slavery to become a great American reformer and educator, giving hope and dignity to himself and to his race. Like these great role models, Legson wanted to serve mankind, to make a difference in the world.

To realize his goal, he needed a first-rate education. He knew the best place to get it was in America. Forget that Legson didn’t have a penny to his name or a way to pay for his ship fare.

Forget that he had no idea what college he would attend or if he would even be accepted. Forget that Cairo was 3,000 miles away and in between were hundreds of tribes that spoke more than fifty strange languages, none of which Legson knew.

Forget all that. Legson did. He had to. He put everything out of his mind except the dream of getting to the land where he could shape his own destiny. He hadn’t always been so determined.

As a young boy, he sometimes used his poverty as an excuse for not doing his best at school or for not accomplishing something. I am just a poor child, he had told himself. What can I do?

Like many of his friends in the village, it was easy for Legson to believe that studying was a waste of time for a poor boy from the town of Karongo in Nyasaland.

Then, in books provided by missionaries, he discovered Abraham Lincoln and Booker T. Washington. Their stories inspired him to envision more for his life, and he realized that an education was the first step.

So he conceived the idea for his walk. After five full days of trekking across the rugged African terrain, Legson had covered only 25 miles. He was already out of food, his water was running out, and he had no money.

To travel the distance of 2,975 additional miles seemed impossible. Yet to turn back was to give up, to resign himself to a life of poverty and ignorance. I will not stop until I reach America, he promised himself. Or until I die trying.

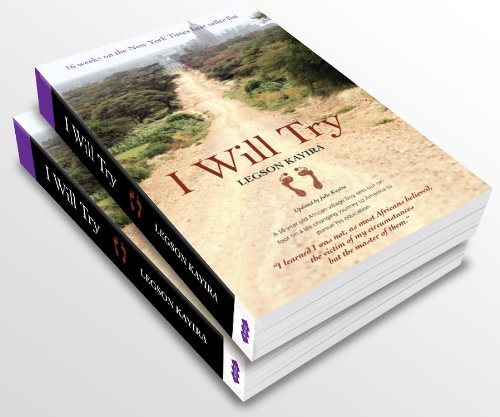

“I learned I was not, as most Africans believed, the victim of my circumstances, but the master of them” – Legson Kayira

Sometimes he walked with strangers. Most of the time he walked alone. He entered each new village cautiously, not knowing whether the natives were hostile or friendly. Sometimes he found work and shelter.

Many nights he slept under the stars. He foraged for wild fruits and berries and other edible plants. He became thin and weak. A fever struck him and he fell gravely ill.

Kind strangers treated him with herbal medicines and offered him a place to rest and convalesce. Weary and demoralized, Legson considered turning back. Perhaps it was better to go home, he reasoned, than to continue this seemingly foolish journey and risk his life.

Instead, Legson turned to his two books, reading the familiar words that renewed his faith in himself and in his goal. He continued on.

On January 19, 1960, fifteen months after he began his perilous journey, he had crossed nearly a thousand miles to Kampala, the capital of Uganda. He was now growing stronger in body and wiser in the ways of survival.

He remained in Kampala for six months, working at odd jobs and spending every spare moment in the library, reading voraciously. In that library he came across an illustrated directory of American colleges.

One illustration in particular caught his eye. It was of a stately, yet friendly looking institution, set beneath a pure blue sky, graced with fountains and lawns, and surrounded by majestic mountains that reminded him of the magnificent peaks back home in Nyasaland.

Skagit Valley College in Mount Vernon, Washington, became the first concrete image in Legson’s seemingly impossible quest. He wrote immediately to the school’s dean explaining his situation and asking for a scholarship.

Fearing he might not be accepted at Skagit, Legson decided to write to as many colleges as his meager budget would allow. It wasn’t necessary. The dean at Skagit was so impressed with Legson’s determination he not only granted him admission but also offered him a scholarship and a job that would pay his room and board.

Another piece of Legson’s dream had fallen into place – yet still more obstacles blocked his path.

Legson needed a passport and a visa, but to get a passport, he had to provide the government with a verified birth date. Worse yet, to get a visa he needed the round-trip fare to the United States.

Again, he picked up pen and paper and wrote to the missionaries who had taught him since childhood. They helped to push the passport through government channels. However, Legson still lacked the airfare required for a visa.

Undeterred, Legson continued his journey to Cairo believing he would somehow get the money he needed. He was so confident he spent the last of his savings on a pair of shoes so he wouldn’t have to walk through the door of Skagit Valley College barefoot.

Months passed, and word of his courageous journey began to spread. By the time he reached Khartoum, penniless and exhausted, the legend of Legson Kayira had spanned the ocean between the African continent and Mount Vernon, Washington.

The students of Skagit Valley College, with the help of local citizens, sent $650 to cover Legson’s fare to America. When he learned of their generosity, Legson fell to his knees in exhaustion, joy, and gratitude.

In December 1960, more than two years after his journey began, Legson Kayira arrived at Skagit Valley College. Carrying his two treasured books, he proudly passed through the towering entrance of the institution.

But Legson Kayira didn’t stop once he graduated. Continuing his academic journey, he became a professor of political science at Cambridge University in England and a widely respected author.

His autobiography, I Will Try, was on the New York Times bestseller list for 16 weeks after its publication in 1965.

Like his heroes, Abraham Lincoln and Booker T. Washington, Legson Kayira rose above his humble beginnings and forged his own destiny. He made a difference in the world and became a magnificent beacon whose light remains as a guide for others to follow.

“I learned I was not, as most Africans believed, the victim of my circumstances but the master of them.” Legson Kayira

People who do the impossible, like Legson, never quit because they know that they will succeed if they keep at it – they have the DESIRE, the PERSISTENCE and they TAKE ACTION. They want things to work out. They are creating for themselves and for others and this is what being here is all about.

YOU CAN DO THE SAME.

Once you understand the power you possess you can change your life like Legson did. He tapped into his manifesting powers and so can you. Interested in learning more? Check out this Manifesting Power Video.